You Too Can Go Down in History as a Pejorative Term

Nothing symbolizes an opposition movement, or galvanizes an audience around it, like a cause célèbre – be it a battle, martyr, or villain -- and the Anti-Scrape adherents found all three in the clash over St. Albans Cathedral and Abbey. Already established as a monastery by the 8th century, St. Albans  grew to be one of the oldest and most beloved religious buildings in the British Isles, eventually serving as both a parish church and, in the chapel, a local grammar school. By the early 19th century, however, the cathedral was in dire need of major repairs, and even after a round of extensive upgrades, it was again desperate for structural work by the 1850s to prevent the apse and leaning central tower from collapsing. A restoration committee began relatively benign reconstruction under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott, one of the leading architects of the Gothic Revival movement, but when Scott died in 1878, the future of St. Albans was thrown into question.

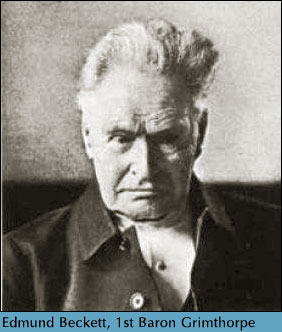

Enter a new member of the St. Albans restoration committee: Sir Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe. Beckett was not only a lawyer and amateur horologist (he designed the mechanism for Big Ben), but also an honorary member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Highly opinionated, and very wealthy, he commandeered the restoration of St. Albans by proposing a new high-pitched roof and neo-Gothic west front, among other alterations.

grew to be one of the oldest and most beloved religious buildings in the British Isles, eventually serving as both a parish church and, in the chapel, a local grammar school. By the early 19th century, however, the cathedral was in dire need of major repairs, and even after a round of extensive upgrades, it was again desperate for structural work by the 1850s to prevent the apse and leaning central tower from collapsing. A restoration committee began relatively benign reconstruction under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott, one of the leading architects of the Gothic Revival movement, but when Scott died in 1878, the future of St. Albans was thrown into question.

Enter a new member of the St. Albans restoration committee: Sir Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe. Beckett was not only a lawyer and amateur horologist (he designed the mechanism for Big Ben), but also an honorary member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Highly opinionated, and very wealthy, he commandeered the restoration of St. Albans by proposing a new high-pitched roof and neo-Gothic west front, among other alterations.  Not surprisingly, Morris and the newly formed SPAB were aghast at the radical changes. However, when they pleaded their case to the restoration committee, Beckett trumped them by simply announcing that if his ideas were approved, he would pay for the work himself. It was an offer the church and city fathers could not refuse.

Critics still debate the architectural merits of the changes wrought by Beckett – especially in the more sensitive ways they were eventually carried out, as well as what the alternative might have been – but at the time St. Albans became the poster child for ham-handed “restoration” of early buildings. Moreover, Beckett’s arrogance and self-styled authority was quickly recast in the public mind as the verb “grimthorp” – a synonym for misguided restoration or even destruction. As late as 1905, the letters page of The Antiquary, a British journal devoted to the study of the past, noted in a typical report that, “It is pleasant to learn that an unexpected hindrance has arisen to prevent, or at all events to check, the grimthorping of the church at Chapel-en-le-Frith. It is now contended, with apparently much reason, that the sum of 2,000 [British pounds] left by the late Mr. Samuel Needham upon trust towards ‘repairing, renewing, or restoring the fabric of the parish church’ cannot be used for the purposes of demolition.”

Remuddling in the 21st Century

Morris’s views on building preservation were not as radical as Ruskin’s, and are what have achieved widespread acceptance in our own time. Moreover, though the main concerns of Morris and the Society he founded were cathedrals, priories, and other large, public, ecclesiastical buildings, scholars have noted that their interests and efforts were predominantly rural – that is, protecting and saving country churches and the like. This became an important link to recognizing the architectural integrity of houses.

In many ways, we have Philip Webb to thank for looking at the architecture of houses in a historic light. Webb pioneered the interest in vernacular buildings in Britain, both as a member of the SPAB and as a practicing architect, and it is through his research, and the canon of techniques he developed for sensitive repair, that others began to embrace the appreciation of houses from particular periods. At about the same time, the United States was celebrating its centennial, and for the first time viewing some of its own, Colonial-era building stock as historic. The earliest American preservation efforts centered on the rescue of one-of-a-kind historic residences – beginning with George Washington’s home Mount Vernon in 1853– but by the time of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, historic building preservation had taken on a much broader, better-defined scope, and with it came the increased use of the word remuddling.

Not surprisingly, Morris and the newly formed SPAB were aghast at the radical changes. However, when they pleaded their case to the restoration committee, Beckett trumped them by simply announcing that if his ideas were approved, he would pay for the work himself. It was an offer the church and city fathers could not refuse.

Critics still debate the architectural merits of the changes wrought by Beckett – especially in the more sensitive ways they were eventually carried out, as well as what the alternative might have been – but at the time St. Albans became the poster child for ham-handed “restoration” of early buildings. Moreover, Beckett’s arrogance and self-styled authority was quickly recast in the public mind as the verb “grimthorp” – a synonym for misguided restoration or even destruction. As late as 1905, the letters page of The Antiquary, a British journal devoted to the study of the past, noted in a typical report that, “It is pleasant to learn that an unexpected hindrance has arisen to prevent, or at all events to check, the grimthorping of the church at Chapel-en-le-Frith. It is now contended, with apparently much reason, that the sum of 2,000 [British pounds] left by the late Mr. Samuel Needham upon trust towards ‘repairing, renewing, or restoring the fabric of the parish church’ cannot be used for the purposes of demolition.”

Remuddling in the 21st Century

Morris’s views on building preservation were not as radical as Ruskin’s, and are what have achieved widespread acceptance in our own time. Moreover, though the main concerns of Morris and the Society he founded were cathedrals, priories, and other large, public, ecclesiastical buildings, scholars have noted that their interests and efforts were predominantly rural – that is, protecting and saving country churches and the like. This became an important link to recognizing the architectural integrity of houses.

In many ways, we have Philip Webb to thank for looking at the architecture of houses in a historic light. Webb pioneered the interest in vernacular buildings in Britain, both as a member of the SPAB and as a practicing architect, and it is through his research, and the canon of techniques he developed for sensitive repair, that others began to embrace the appreciation of houses from particular periods. At about the same time, the United States was celebrating its centennial, and for the first time viewing some of its own, Colonial-era building stock as historic. The earliest American preservation efforts centered on the rescue of one-of-a-kind historic residences – beginning with George Washington’s home Mount Vernon in 1853– but by the time of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, historic building preservation had taken on a much broader, better-defined scope, and with it came the increased use of the word remuddling.

grew to be one of the oldest and most beloved religious buildings in the British Isles, eventually serving as both a parish church and, in the chapel, a local grammar school. By the early 19th century, however, the cathedral was in dire need of major repairs, and even after a round of extensive upgrades, it was again desperate for structural work by the 1850s to prevent the apse and leaning central tower from collapsing. A restoration committee began relatively benign reconstruction under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott, one of the leading architects of the Gothic Revival movement, but when Scott died in 1878, the future of St. Albans was thrown into question.

Enter a new member of the St. Albans restoration committee: Sir Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe. Beckett was not only a lawyer and amateur horologist (he designed the mechanism for Big Ben), but also an honorary member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Highly opinionated, and very wealthy, he commandeered the restoration of St. Albans by proposing a new high-pitched roof and neo-Gothic west front, among other alterations.

grew to be one of the oldest and most beloved religious buildings in the British Isles, eventually serving as both a parish church and, in the chapel, a local grammar school. By the early 19th century, however, the cathedral was in dire need of major repairs, and even after a round of extensive upgrades, it was again desperate for structural work by the 1850s to prevent the apse and leaning central tower from collapsing. A restoration committee began relatively benign reconstruction under the direction of Sir George Gilbert Scott, one of the leading architects of the Gothic Revival movement, but when Scott died in 1878, the future of St. Albans was thrown into question.

Enter a new member of the St. Albans restoration committee: Sir Edmund Beckett, 1st Baron Grimthorpe. Beckett was not only a lawyer and amateur horologist (he designed the mechanism for Big Ben), but also an honorary member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Highly opinionated, and very wealthy, he commandeered the restoration of St. Albans by proposing a new high-pitched roof and neo-Gothic west front, among other alterations.  Not surprisingly, Morris and the newly formed SPAB were aghast at the radical changes. However, when they pleaded their case to the restoration committee, Beckett trumped them by simply announcing that if his ideas were approved, he would pay for the work himself. It was an offer the church and city fathers could not refuse.

Critics still debate the architectural merits of the changes wrought by Beckett – especially in the more sensitive ways they were eventually carried out, as well as what the alternative might have been – but at the time St. Albans became the poster child for ham-handed “restoration” of early buildings. Moreover, Beckett’s arrogance and self-styled authority was quickly recast in the public mind as the verb “grimthorp” – a synonym for misguided restoration or even destruction. As late as 1905, the letters page of The Antiquary, a British journal devoted to the study of the past, noted in a typical report that, “It is pleasant to learn that an unexpected hindrance has arisen to prevent, or at all events to check, the grimthorping of the church at Chapel-en-le-Frith. It is now contended, with apparently much reason, that the sum of 2,000 [British pounds] left by the late Mr. Samuel Needham upon trust towards ‘repairing, renewing, or restoring the fabric of the parish church’ cannot be used for the purposes of demolition.”

Remuddling in the 21st Century

Morris’s views on building preservation were not as radical as Ruskin’s, and are what have achieved widespread acceptance in our own time. Moreover, though the main concerns of Morris and the Society he founded were cathedrals, priories, and other large, public, ecclesiastical buildings, scholars have noted that their interests and efforts were predominantly rural – that is, protecting and saving country churches and the like. This became an important link to recognizing the architectural integrity of houses.

In many ways, we have Philip Webb to thank for looking at the architecture of houses in a historic light. Webb pioneered the interest in vernacular buildings in Britain, both as a member of the SPAB and as a practicing architect, and it is through his research, and the canon of techniques he developed for sensitive repair, that others began to embrace the appreciation of houses from particular periods. At about the same time, the United States was celebrating its centennial, and for the first time viewing some of its own, Colonial-era building stock as historic. The earliest American preservation efforts centered on the rescue of one-of-a-kind historic residences – beginning with George Washington’s home Mount Vernon in 1853– but by the time of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, historic building preservation had taken on a much broader, better-defined scope, and with it came the increased use of the word remuddling.

Not surprisingly, Morris and the newly formed SPAB were aghast at the radical changes. However, when they pleaded their case to the restoration committee, Beckett trumped them by simply announcing that if his ideas were approved, he would pay for the work himself. It was an offer the church and city fathers could not refuse.

Critics still debate the architectural merits of the changes wrought by Beckett – especially in the more sensitive ways they were eventually carried out, as well as what the alternative might have been – but at the time St. Albans became the poster child for ham-handed “restoration” of early buildings. Moreover, Beckett’s arrogance and self-styled authority was quickly recast in the public mind as the verb “grimthorp” – a synonym for misguided restoration or even destruction. As late as 1905, the letters page of The Antiquary, a British journal devoted to the study of the past, noted in a typical report that, “It is pleasant to learn that an unexpected hindrance has arisen to prevent, or at all events to check, the grimthorping of the church at Chapel-en-le-Frith. It is now contended, with apparently much reason, that the sum of 2,000 [British pounds] left by the late Mr. Samuel Needham upon trust towards ‘repairing, renewing, or restoring the fabric of the parish church’ cannot be used for the purposes of demolition.”

Remuddling in the 21st Century

Morris’s views on building preservation were not as radical as Ruskin’s, and are what have achieved widespread acceptance in our own time. Moreover, though the main concerns of Morris and the Society he founded were cathedrals, priories, and other large, public, ecclesiastical buildings, scholars have noted that their interests and efforts were predominantly rural – that is, protecting and saving country churches and the like. This became an important link to recognizing the architectural integrity of houses.

In many ways, we have Philip Webb to thank for looking at the architecture of houses in a historic light. Webb pioneered the interest in vernacular buildings in Britain, both as a member of the SPAB and as a practicing architect, and it is through his research, and the canon of techniques he developed for sensitive repair, that others began to embrace the appreciation of houses from particular periods. At about the same time, the United States was celebrating its centennial, and for the first time viewing some of its own, Colonial-era building stock as historic. The earliest American preservation efforts centered on the rescue of one-of-a-kind historic residences – beginning with George Washington’s home Mount Vernon in 1853– but by the time of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, historic building preservation had taken on a much broader, better-defined scope, and with it came the increased use of the word remuddling.